By Jamaine Krige

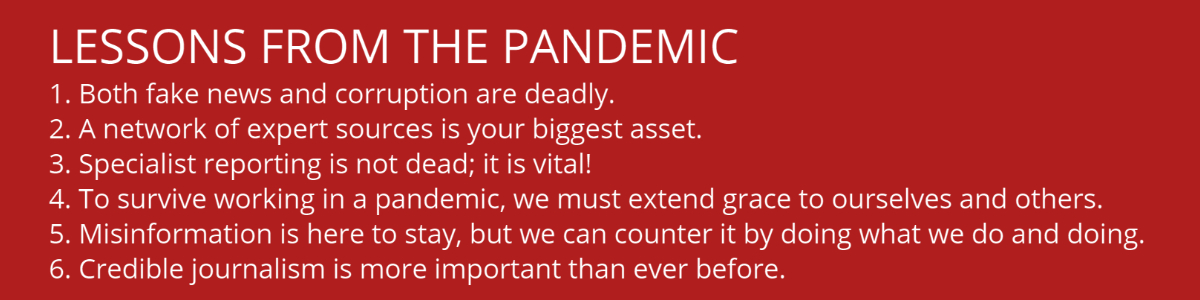

The Covid-19 pandemic has justifiably dominated news headlines for more than a year. While it remains an important local, national and global story, it’s not the only one to tell. The industry must take the lessons learned over the past year forward for maximum impact in a post-Covid news environment.

Safura Karim says that this is an important conversation to have as the pandemic has not only changed the information landscape, but also how media practitioners and the public engage with that information. All three women believe that the lessons learned during the pandemic, if internalised, will strengthen the industry going forward.

Ina says, at the start of the pandemic, one of the major challenges was the sheer amount of information available. “While in lockdown everyone was suddenly an epidemiologist and knew everything about everything,” she laughs. “It was amazing!” She busied herself with sifting through the information available and establishing whether it was science-based or not, no mean feat with the overwhelming amount of content out there.

“One of the first things we did was to set up a database of people who we knew had been working on coronaviruses for a very long time. If anything came up that I was unsure of, I was able to tap into these resources,” she explains. There is a need for journalists to have contacts to help you figure out what is true and what is accurate.

Collaboration and support within the industry is also important. “Just because we’re in different newsrooms does not mean we are in direct competition; we should use the networks we have,” says Ina.

OVERCOMING NEWS DELIVERY CHALLENGES

Pauli recalls that the start of the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown brought two major challenges. The first was a freedom of physical movement, which made it difficult for journalists to work. “It was difficult to see sources, especially as investigative journalists. We often have face-to-face meetings because people are hesitant to use technology or say things that may be recorded. It was difficult to work but we could understand it, and the bigger purpose it served.”

The second constraint, however, is the one that carries an important lesson and must be remembered going forward. Pandemics and other disasters open up opportunities for governments to clamp down on media freedom, even as accurate information is needed most. During the pandemic, there was “a sudden shift from government in information that was being shared, and how that sharing was being facilitated. “, she says.

“Journalism is a pillar of undeniable strength in South Africa and we should all care more about it, especially the freedom of journalists to do their work,” she says. “We have always been aware of that, but I think it was amplified during Covid and emphasised with the clampdown of information that we suddenly had to work with.”

Despite these challenges, journalists, specifically health and investigative reporters, rose to the challenge and did exceptionally well. “Publications like Bhekisisa and Maverick Citizen did extraordinary work under very difficult circumstances, and one could see the deep knowledge there; they really know their stuff!”

But, she acknowledges, these publications had been reporting on viruses, disease and various other health concerns for many years, “where the rest of us did not have the knowledge or the background”. This highlighted the knowledge gap in general reporting that she believes needs to be filled. “We became aware that health is an issue sector that we really need to focus on,” she explains.

SPECIALIST SKILLS DURING TIMES OF CRISIS

Beat reporting has lost popularity in recent years due to understaffing, lack of resources and the attrition of senior reporters in newsrooms. The Covid-19 crisis has, however, showed that there is still a place for specialist reporting, and beat-specific training like that offered by fraycollege. And, as Ina notes, sometimes even specialist knowledge is not enough. “One thing I realised is that even though I had been reporting on health for ten years, there were still gaps and blind spots in my knowledge.”

Pauli says it was a steep learning curve. “We also learned the value of open-source investigations, where you sit at your desktop and the only information you have is what is available online or on telephone from various experts or knowledgeable people,” she explains.

In South Africa, “journalism by Pieter-Louis Myburgh is an excellent example of how to do open-sourced investigations. He took company information and public-private enterprise information given to us by the government and realised that a very lucrative contract was given to people very close to our health minister.”

A Special Investigative Unit enquiry has begun to look into his findings. “So we realised that even with the constraints, there is still so much to do, and so much we can do.” Taking these lessons forward, she says, means we can continue to strengthen our reporting and our resolve. “This is why we exist – because the government can always do better and we need to stand up for the people. This is what made life difficult during Covid-19, but also made it worth living, and worth being a journalist during these times.”

Both Ina and Pauli agree that the pandemic has proved that South Africa has not only world-class journalists, but also world-class scientists.

MORE THAN COVID-19 AND BIGGER THAN HEALTH

The pandemic has also been a stark reminder that reporting about health is so much bigger than reporting on illness or disease. “One of the biggest misconceptions about health journalism is that it is just about health, while it’s actually about life.” It affects every aspect of life. “We cannot separate health from politics or economics or the environment, because they are all interlinked. It’s not just a medical thing,” she explains. “We need to look at linking government corruption directly to people dying, because that is what is happening.”

According to Ina, one of the biggest Covid successes was their ability to rally colleagues from across the continent. “When this started, we worked in six countries across Africa and tried to coordinate a Covid news diary.” This at a time when everything was uncertain, and not just professionally. “Yes, we are journalists, but we are human first. We were thrown into a situation, while everybody tried to make sure people had food to eat and a place to go, we still had to function to get news out there,” she says. “And while doing so, to acknowledge that it’s not just you who is in hospital, but maybe my mom is there too.”

She smiles. “It was so important to remember that this is a pandemic. We have to extend grace – to ourselves and to others.”

GRACE AND SELF-CARE

While the successes were important, Pauli says the truly valuable lessons that she will be taking forward come from her failures. “They were much more significant and magnificent than my successes,” she laughs. Like Ina, it was important to sometimes remind herself that this was not business as usual. “It is a pandemic, and mental health was a big thing for me,” she admits. “I think the pandemic had a compounding effect for things that happened in other investigations that I was busy with., It was quite an awakening that the country’s most popular politicians would call you out repeatedly or would call you Satan or a witch, or the dog-whistling that would cause rape threats and saying that you should be hanged…” The threats against her are numerous, graphic and well-documented. “Those things in the context of a pandemic had a compounding effect on me. I had to work really really hard to just be okay, and to ensure that I could keep working. At times it was touch and go…”

While she initially viewed this inability to close herself off from the outside world and focus only on work as a failure, it also led to successes, both personally and professionally. “I actually did, in the end, manage to heal, but also to learn how to deal with things better,” she says.

MORE MUST BE DONE

Pauli acknowledges that the media has done particularly well in these unprecedented times, but feels that this is not enough. ““In an ideal world we will correct the government and right the wrongs; we will be successful and we will have a functional government.” But this is not an ideal world. “And this is why we can never do enough. We need to chip away at this and be brilliant at what we do everyday,” she says. “We now need to use the lessons that we have learnt and are learning to ensure that we are doing our people justice going forward; as we move to ensure that we hopefully have a functioning NHI, or an NHI that in some form or another will benefit the people of the country – corruption free.”

The truth of the matter, she says, is that Covid-19 has greatly impacted on South Africa’s health response in general, and had severe ramifications of the expendability of other programmes. “According to my sources we will not reach our 2030 deadline for implementing the NHI – there is no money for it,” she says. “We need to recover – those are the words of the people in Treasury that I spoke to. We need to focus on healing first and recovering from Covid before we can start spending again on something like the NHI.” But in this recovery lies and important duty and opportunity for journalists. “It’s important that that healing process is documented, and that we shine a light on it, as well as on processes like the distribution of the Biovac tenders,” she explains. “That will give us a very good indication of how the NHI will develop, what we will need to focus on and how efficient the NHI setup will be.”

ENSURING ACCURACY IS A COLLABORATIVE PROCESS

Another key lesson during this time was the need for accuracy. “I always said health journalism is a matter of life and death, and people would roll their eyes at that,” says Ina. “But now we see what miscommunication and misinformation really means; that it can have further repercussions.” She believes that part of the vaccine-hesitancy seen at the moment is due to this, and because people don’t understand the information they come into contact with. “That is why it is important for us as journalists to understand the information, so that we can translate that knowledge.” This, she says, is something that journalists should take forward in their future reporting.

Safura wonders whether the pandemic has brought scientists and journos closer, improving knowledge translation and dissemination. Or did it have the opposite effect, exacerbating the spread of misinformation and disinformation?

Ina thinks it’s the former. “We could text experts in the middle of the night and they would rise to the challenge,” she recalls. “They availed themselves to us while they were also trying to figure this out, because none of us has been here before. I feel we went on a journey together.” The science community was transparent in their interactions. “They were very open about their own experiences, about what they knew and what not.” These interactions built trust between the two groups. “I also dealt with a lot of first time sources, which made them more comfortable. Hopefully coming out of Covid we will see more public engagement with the scientists,” she says.

MISINFORMATION IS HERE TO STAY

This, says Pauli, should also help counter the wave of disinformation and misinformation out there. “It was an absolute awakening to fake news when I realised my parents, family and close friends were a perfect example of what was happening in South Africa in the broader community, and what the public believed,” she remembers. She initially responded with anger when they shared screenshots or messages consisting of ‘nonsense and conspiracy theories’. “I had to tell myself to be calm, debunk the myths and remind them not to believe everything they see on social media.” The situation has improved since then with journalists and experts speaking out on social media, leading to an uptake in people’s need for credible information.

Despite this ‘awakening’, Pauli says we must be careful not to regress: “Life is never going back to what it was, and we need to remind people that misinformation is here to stay.”

Ina agrees that this is a battle that has not yet been won. “The only way we can counter misinformation is literally just by doing what we do and by doing it well.”

When it comes to health, ‘doing what we do and doing it well’ extends beyond just reporting on Covid-19. Pauli, Ina and Safura hope that journalists will use the lessons from the pandemic to drive their efforts going forward. Health reporting today can be predictive of focus-areas for journalists going forward, and highlight systemic shortcomings that should be monitored.

Jamaine Krige

Award-Winning Journalist; Editor; Storyteller; Trainer