By Jamaine Krige

There was no way to predict the societal, national and global disruptions that lay ahead. With the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, every aspect of life as we knew it changed. This included disruptions to the news and media landscape, the way media practitioners and media organisations operate, as well as the way the public engaged with the news of the day. But if so much could change in just one year, what can the industry and industry leaders do to prepare themselves and their teams for the newsrooms of the future?

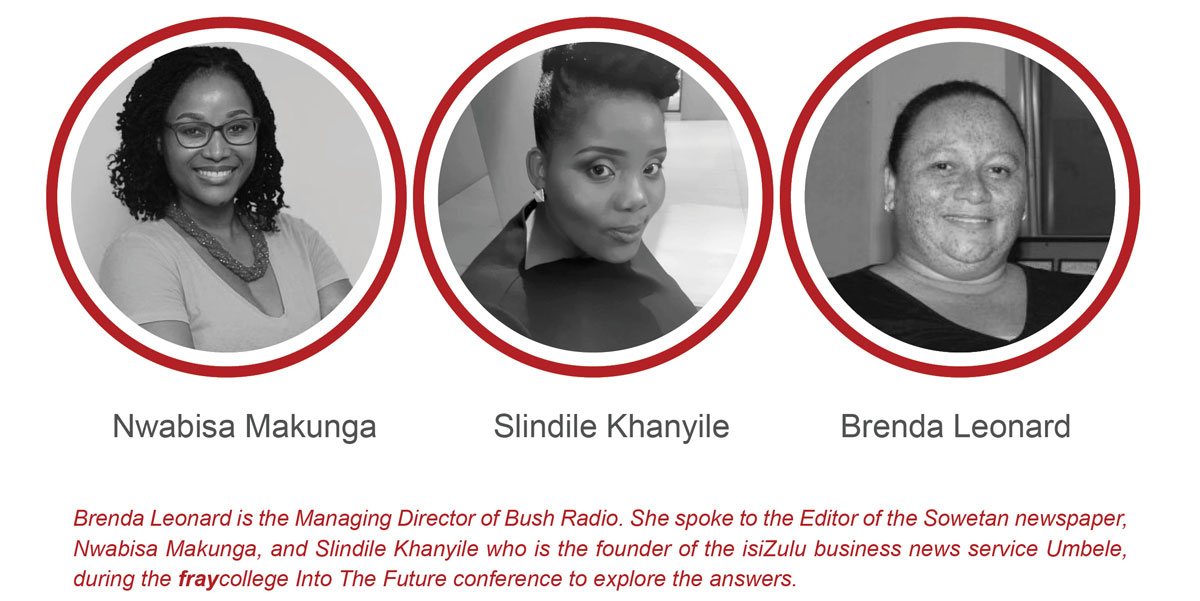

While the Covid-19 pandemic has caused a complete disruption to many workplace practices, including those in the newsroom, three media experts agree that it has also given impetus to many changes that were already underway in the media industry.

Nwabisa Makunga says although this has posed a challenge, it also presented an opportunity for real progress. “The pandemic forced us to do what we knew we had to do over the next 10 years, but in the space of two weeks,” she explains.

“It forced us to get our newsrooms in shape to work remotely and virtually, to keep communication going and to still produce content of the highest quality, even from the different spaces that we were in.”

She says this was not an easy task. It required a lot of immediate investment in technology, and forced leaders to think differently about workflows, the way content is produced and the innovation needed to thrive in this new environment. In that way, the pandemic brought the future envisioned for the newsroom to the doorstep much sooner than anticipated

DIGITAL DIVIDE

While digital processes and digitisation have been a hot topic in the media sector before, the pandemic forced many newsrooms to stop talking, and start acting.

Brenda Leonard notes that this has, however, also shined a spotlight on the major digital divides that still exist, both in South Africa and on the continent, which has to do with more than just audience access. “It also includes the digital divide in the newsrooms,” she explains.

“Community media organisations sometimes have just one computer, which is shared between the sales department to do quotes, the admin team and the newsroom!” The difficult situation was thus complicated as the pandemic spread. “We just weren’t equipped to work from home. It took time to get to that point because everyone didn’t necessarily have access to equipment,” she remembers. “This is the digital divide when we talk about future newsrooms.”

Slindile Khanyile agrees that this is something that needs to be addressed, but media organisations cannot overcome this in isolation. “If there is one thing that the government could do for us as a sector – this is it! For us to see a significant improvement or change, we require a regulatory environment that will enable that change.”

While strides have been made in some countries, for example, reducing the cost of data, these changes are not enough. She says infrastructure remains a massive problem. “In some cases, it’s not even that people aren’t aware of information available online or in the digital space, but rather that they live in areas with no network coverage.”

This, she adds, was glaringly obvious during South Africa’s first hard lockdown when learners across the country had to migrate to remote and online learning. “This problem, in all industries and at all levels of our society, needs to be addressed because it is far bigger than the situation in our newsrooms.”

NICHE MEDIA SPACES

Brenda says despite the challenges of Covid-19 and the digital divide, the pandemic also brought with it a variety of opportunities: accelerated digitisation of workflows, cost-saving, improving diversity and accessibility.

Perhaps most surprising is the surge in audience, engagement – something that the industry should fight to maintain and to grow going forward. “At Bush Radio we found that because our audiences were at home, they engaged with the station more than before; also during times when engagement would normally drop because people were at work,” she says.

If organisations want to transcend traditional media and step into the future newsrooms, then the opportunities brought by the pandemic must be embraced. According to Nwabisa important lessons were learnt during the changes over the past year. “It’s difficult to predict with certainty what the future newsroom will look like. We know, however, due to current trends, especially in the mainstream media space, that we have been dealt a blow that has been a long time coming,” she says. “Last year we all had to take a step back and look at how to innovate.

That’s where people like Slindile have really hit the nail on the head, because the future of media lies very much in niche spaces. We have to realise that we cannot be all things to all men,” she laughs. “What we do, we need to do right – the platforms we choose, the content we create, the people we identify with – and in Slindile’s case, that is business news in isiZulu.” Nwabisa says media leaders need to decide what gap they are filling and who they are speaking to, and then really commit to catering to those audiences. “We cannot keep stretching ourselves as we have done the last couple of years. The absolute decimation of resources seen in the newsroom means we need to be deliberate and calculated in what we choose and how we execute those choices.”

Slindile agrees, saying media organisations could use data and analytics to help answer those questions. “We are going to move away from assuming what our readers want,” she predicts. “We need to use the benefit of the data we have available; we publish in isiZulu so could easily assume that visitors to our site come from KwaZulu Natal.” This, however, is not the case,as the biggest audience comes from Gauteng, with a spread of regular readers, the majority being women, in seven of the nine provinces. “We must use this data to plan. If the data tells us that what we’re currently doing is not working, we need to be bold enough to move away and give our audiences what they want,” she says.

‘TALK TO ME IN MY OWN LANGUAGE’

Popular to contrary belief, Slindile adds, audiences do want high-quality content in languages other than English. Nwabisa agrees, stating that the common misconception that people prefer their news in English is not a valid one. Rather than an issue of preference, she says it is often an issue of access. “Whatever was produced was not necessarily in people’s own languages, and they lacked the option to choose a different language of delivery. Today, there are opportunities to develop that niche, particularly in storytelling, because there is so much nuance that is only possible if a story is captured and delivered in someone’s own language. This knowledge opens so many doors.” Delivering content in this way is therefore not only an opportunity for audience access, but also a business opportunity.

This is, of course, a business opportunity that Slindile has tapped into. “We are proof that people do want specialised news, not just general news. And they want it in their own language.” There is also a new isiZulu sports publication that has been launched in South Africa. “I think we will see more niche indigenous-language publications, because the beauty of technology and digital publishing is that it somehow levels the playing field, reducing the cost of starting and maintaining a publication, especially when you think about what was previously needed for print publications in terms of infrastructure and distribution… Digital helps us bridge that divide and deliver what people want.”

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

At Umbele, Slindile says it is easy for them to deliver on their audience expectations because the team is clear in who they are as a brand and what they strive for. “Our audiences are people who want to consume business news in isiZulu,” she says. As a small niche newsroom, they decided early on that they would not compete with other, more established publications as they did not have the resources or capacity to drive breaking news. “We want to tell a different story. We will, therefore, lreport the GDP figures released yesterday, but look at it from a different perspective. In this sense it helps to be focused and localised.”

It also gives them a chance to draw in more readers and appeal to a larger audience, many who feel that they are marginalised and that their stories are not told. “We don’t just look at businesses generating millions,” she says. “Stories about a vendor selling fat cakes on the roadside… if we think that story is special and should be told, and that someone could draw inspiration from it, then it is a story we will tell. When people feel seen, heard and recognised, it goes a long way.”

Nwabisa says this has also been evident at the Sowetan newspaper. Despite being an iconic national brand that still chases the big stories that affect the country, their audience yearn for more.

State capture is important, she says, but adds that “we’ve learned that what they want from us is to capture the heart of Soweto, the heart of Mamelodi… We’ve had to localise our journalism, and the gap we fill is to link what happens on a national stage – politics, business and economics – to what happens to people on the ground.” The response to real stories of real people has been overwhelming. “For us, this is a formula that works.”

GOOD ETHICAL REPORTING

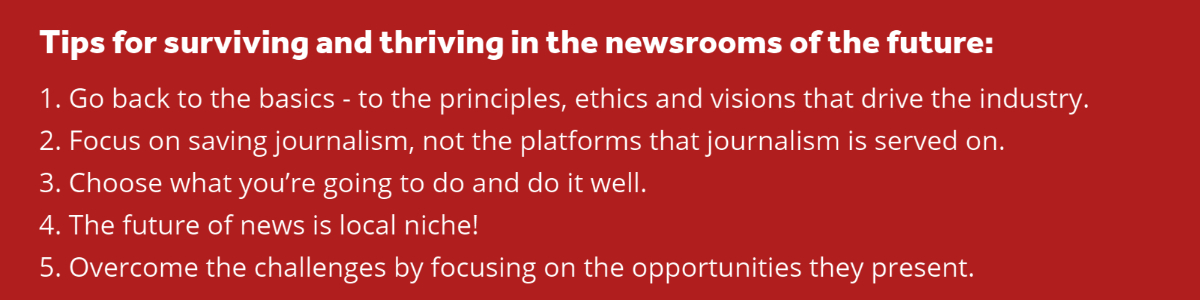

This formula thus recognises that niche is the future and that localisation is necessary, but also factors in another key concept and that is good, ethical reporting.

Slindile, Nwabisa and Brenda all agree that journalists must evolve rapidly in terms of technology and technical skills, but stress that the basic principles of solid, credible journalism will always remain priority.

Regardless of what happens, there will always be a need for accurate and fair reporting, and the skills that underlie this. No matter what the platforms and trends of news consumption, people want credible news stories about the community, country and world they live in.

It’s as easy and as complicated as that, the women agree. Slindile, on the other hand, is also quick to acknowledge that everyone is nervous about what the future may hold. “One thing we know for certain is that we want to save journalism,” she adds, “but that doesn’t mean only saving the platforms on which we deliver our content. We need to invest in storytelling, in fact-checking, in those basic things that seem to have fallen away in recent years. Once we get that right, then we will get our audiences again. If people know that we deliver credible news, they will keep coming back. They will be faithful and loyal, because we will be serving them content they can trust and information they can use in their daily lives. That’s what it’s about, isn’t it? We need to save journalism, instead of saving platforms.”

Brenda agrees that, irrespective of the medium or the platform, it is the content that draws audiences back. “And to really master this deliverable, we need to go back to the basics – to the principles, ethics and visions that drive us as an industry.”

Jamaine Krige

Award-Winning Journalist; Editor; Storyteller; Trainer